Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

For a proper understanding of the pre-Raphaelite movement, it is necessary to identify the difference between its individual stages, which stretched over several decades. It should be noted that many foreign historians and critics of art are silently ignoring or deliberately distorting its progressive line, trying to limit the rebelliousness of the Pre-Raphaelites to a purely artistic field.

For a proper understanding of the pre-Raphaelite movement, it is necessary to identify the difference between its individual stages, which stretched over several decades. It should be noted that many foreign historians and critics of art are silently ignoring or deliberately distorting its progressive line, trying to limit the rebelliousness of the Pre-Raphaelites to a purely artistic field.

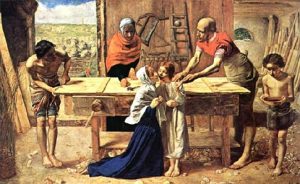

In September 1848, seven young men, students of the school of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in London, formed a “Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood” with the goal of making a revolution in English art. It included the sculptor Thomas Wulner, artists – James Collinson, John Everett Milles, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his brother William Michael Rossetti, Frederick Stephens and William Holman Hunt. They were all young, from nineteen to twenty-one. Artists, in fact, could be called only three: the youngest – Milles, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Holman Hunt.

It was not for nothing that the brotherhood arose in England, the most industrialized country, which overtook other European countries. The struggle with the power of capital turned out to be especially difficult and acute. It was led by the “first workers’ political party” —the Chartists, to which the petty bourgeoisie joined. Chartism arose in the mid-1830s and reached its apogee by 1848 due to the economic crisis and the general revolutionary situation in Europe. These sentiments captured and youth. It should be taken into account, for example, that such Pre-Raphaelite artists, like the Rossetti brothers, belonged to the family of a prominent Italian political émigré, where revolutionaries-Italians were constantly hiding in London. Hunt and Milles themselves directly participated in the Chartist movement, including the major intervention of the Chartists on April 10, 1848. It was brutally suppressed, which was the beginning of the recession of the revolutionary wave.

In the next quarter of a century, the world domination of capitalist England is becoming stronger. It establishes an even more merciless reaction, which determined the short duration of the first most progressive stage of pre-Raphaelitism and the subsequent confusion of its participants.

In the middle of the century, triumphant philistinism prevailed in English art. The artists lost the achievements of the great painters of the 18th and early 19th centuries. The constable died in 1837, and Turner lived out his last years as a recluse. Self-satisfied rich people preferred to buy sugary and respectable ceremonial paintings. Artists were doomed to beg or adapt to the vulgar demands of buyers. This kind of wingless naturalism in England was called “realism.” It was precisely against the cognitive approach to visual production — it was difficult even to call it art — and the Pre-Raphaelite revolt was directed.

The name of the brotherhood itself seemed to imply the recognition of the art of the predecessors of Raphael and the denial of himself. But it is not. The picturesque achievements of the great master were reduced by the followers to the finished recipe. Rafael was unwittingly responsible for the work of later imitators, whose “high style” was distinguished by its mannerism and lack of truth in life.

The Pre-Raphaelite movement began small: the friendship of several young people united in their desire to break free from the stifling atmosphere of the wretched philistine art of the reign of Queen Victoria and the rule of successful capitalists.

Pre-Raphaelitism was a manifestation of a process that affected not only English, but also all European painting. The classical academic tradition collapsed. The new was in the pursuit of sincerity and truth. Struggling for the truth of the senses, the Pre-Raphaelites sought its direct expression not in pathetic theatrical poses, but in restrained, but uniquely individual gestures, spied upon in reality. Denying the blackness of color “under the old masters” and the generalization of the details of the academic school, they tried with equal care to write out the smallest details of the foreground and the most distant objects, not fearing the brightness of colors and not really worrying about their harmonious combination.